First published in Penang Monthly (September 2023).

WANTAN MEE IS a classic dish in Penang. Simple and tasty, it is a safe pick if you are unsure of what to order when eating out. It is usually served with fried or boiled dumplings, or a mix of both. What differs among vendors are also how many dumplings are included in the dish; some “dumplings” are also nothing more than fried dough skin.

Penang hawker food gives the French a run for their money, and hawkers continue to beat expectations about how small portions can be. Penangites are penny-wise regarding hawker food, and the hawkers seem to have recognised this. Extraordinarily, the Butterworth Art Walk organised a RM2 mini-food festival, allowing patrons to savour “smaller portions of hawker food at lower prices”1.

Hock Khoon from Bukit Mertajam laments how Curry Mee used to come with many cockles and side ingredients. “Now it has shrunk a lot. They compensate with more noodles! Some don’t even add cuttlefish.” He also observes how much beef portions have decreased at a major Japanese food outlet in Penang, even as its prices have increased.

This phenomenon, where businesses maintain pricing while reducing the quantity or size of their products, is known as shrinkflation. Named by the Norwegian Language Council as the Word of the Year in 2022 (Krympflasjon in Norwegian), the word was first used in 2015 in its current meaning by economist, Pippa Malmgren. A portmanteau of the words “shrink” and “inflation”, shrinkflation has been referred to in the past as package downsizing, product downsizing and content reduction.

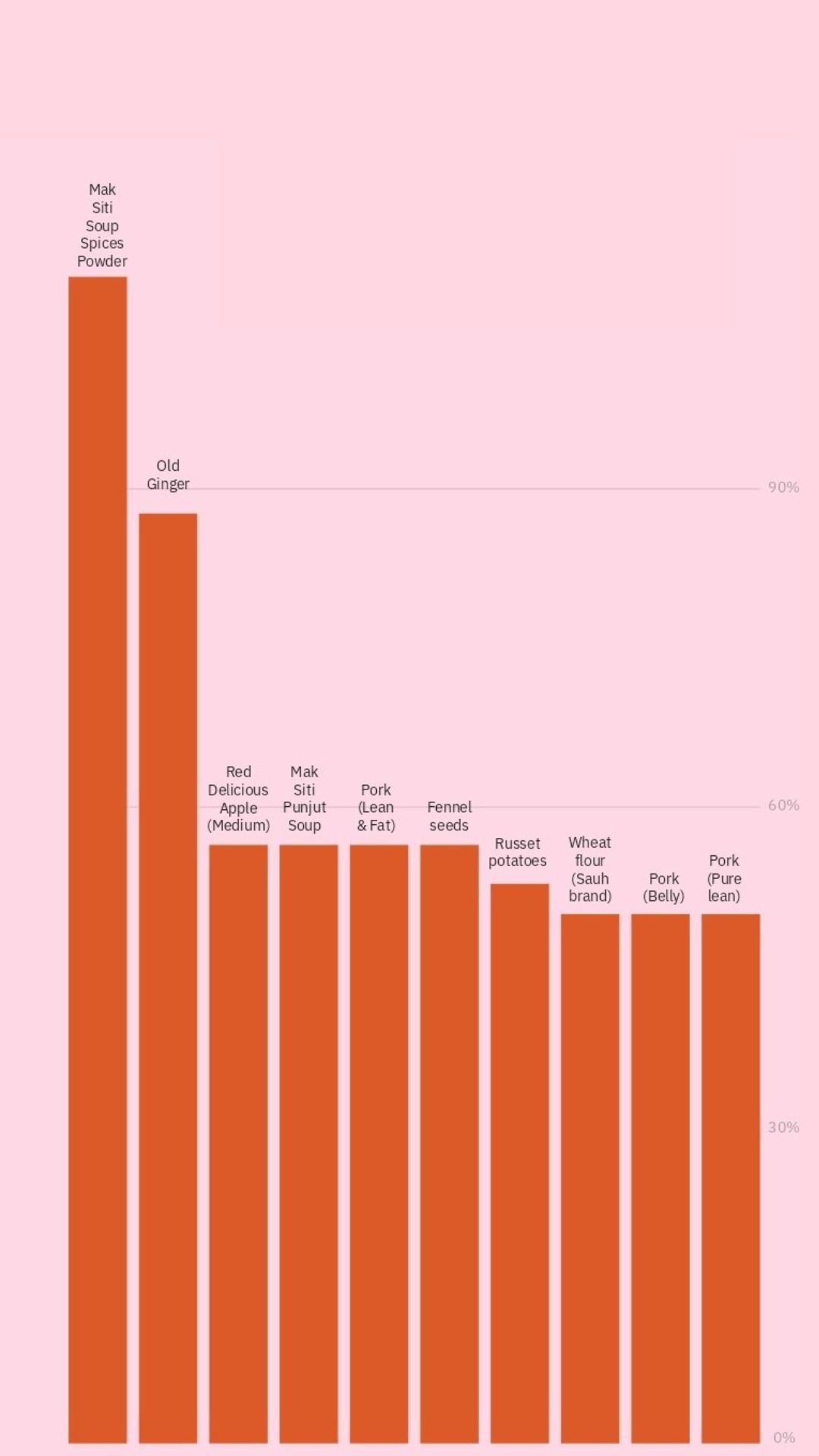

As of June 2023, the food component of Penang’s consumer price index (CPI) has risen by 12.9% since early 2020. In 2022 alone, food prices increased by 6% year-on-year, contributing to 1.8% of Penang’s inflation for the year, up from 0.3% in 2021. Prices for milk, cheese and eggs rose by 11% year-on-year in 2022 (2021: 2.6%), while meat prices increased by 10.5% (2021: 1%). As of now, food price inflation remains elevated across the world amid the Russia-Ukraine conflict, coupled with erratic weather patterns caused by a dangerous combination of climate change and El Nino. The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) notes that lower dam levels in northern Peninsular Malaysia threaten to lower rice yields, while the National Water Service Commission (SPAN) has set up an El Nino “war room” to monitor dam levels.

Different parts of the world have been experiencing shrinkflation differently. In Nigeria, Domino’s launched a “smallie” pizza with just four slices. In Europe, Bloomberg reports that Hamburg’s consumer protection office received three to five times more than the usual number of complaints regarding shrinking product sizes. In Britain, The Economist reports that Cadbury’s Creme Eggs now come in packs of five instead of six.

Why Does This Work?

To many economists, the idea that the economic man (homo economicus) would fall prey to the shrinkflation trick is preposterous. If consumers are rational, should they not respond to a traditional price increase like they would to a price increase disguised as smaller packaging? On the contrary, the market research firm, Nielsen2, claims that consumers respond half as much to a change in prices via downsizing versus a raw price increase, and evidence suggests that shrinkflation does fool consumers.

Some theorise that firms exploit consumers’ inattention, hoping that consumers will not notice the change in quantity at the same price, or perhaps firms try to avoid angering customers by raising prices. In “Does Peter Piper Pick a Package of Pepper Inattentively?” 3, Ian Meeker finds that US consumers did not reduce their purchases in response to the shrinkflation of black pepper. Conversely, in Japan, evidence from store scanner data4 suggests that consumers there do respond to shrinking product sizes.

For certain types of businesses, shrinkflation can be explained by using a pricing strategy known as quantum pricing, where there are significant gaps between prices, and the same prices are used across different types of products over time. Retailers design their products to fit a certain price, which explains why quality (and/or quantity) reduces over time. Aparicio and Rigobon 5 find that large retailers, notably Apple, Zara, H&M, Ikea and Uniqlo, follow this strategy.

What Can We Do?

Given how hard it is to track shrinkflation, consumers have taken matters into their own hands in some parts of the world. A Japanese consumer, Masayuki Iwasa, created a website to track shrinkflation — www.neage.jp — which monitors 400 goods and services. In the US, Edgar Dworsky, founder of consumer advocacy site mouseprint.org, has been cited in the New York Times as the only person documenting shrinkflation in the US.

The Malaysian Minister of Economy, Rafizi Ramli, has encouraged consumers to leverage Department of Statistics’ (DOSM) data to compare price differences across premises using the KitaJaga app. However, the items covered are fairly limited and may not reflect changing consumer preferences. This raises the question of whether or not the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is based on these data, provides a good view of general price changes.

Footnotes

Penang International Food Festival 2018 | Penang Free Sheet↩︎

What is product downsizing and how do you use it? - NIQ (nielseniq.com)↩︎

Meeker, Ian, Does Peter Piper Pick a Package of Pepper Inattentively? The Consumer Response to Product Size Changes (September 14, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3943201 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3943201↩︎

Imai, S. and Watanabe, T. (2014), Product Downsizing and Hidden Price Increases. Asian Economic Policy Review, 9: 69-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12047↩︎

Diego Aparicio & Roberto Rigobon, 2023. “Quantum prices,” Journal of International Economics.↩︎